|

This version is still in development and is not considered stable yet. For the latest stable version, please use Spring Framework 6.0.29! |

Bean Scopes

When you create a bean definition, you create a recipe for creating actual instances of the class defined by that bean definition. The idea that a bean definition is a recipe is important, because it means that, as with a class, you can create many object instances from a single recipe.

You can control not only the various dependencies and configuration values that are to

be plugged into an object that is created from a particular bean definition but also control

the scope of the objects created from a particular bean definition. This approach is

powerful and flexible, because you can choose the scope of the objects you create

through configuration instead of having to bake in the scope of an object at the Java

class level. Beans can be defined to be deployed in one of a number of scopes.

The Spring Framework supports six scopes, four of which are available only if

you use a web-aware ApplicationContext. You can also create

a custom scope.

The following table describes the supported scopes:

| Scope | Description |

|---|---|

(Default) Scopes a single bean definition to a single object instance for each Spring IoC container. |

|

Scopes a single bean definition to any number of object instances. |

|

Scopes a single bean definition to the lifecycle of a single HTTP request. That is,

each HTTP request has its own instance of a bean created off the back of a single bean

definition. Only valid in the context of a web-aware Spring |

|

Scopes a single bean definition to the lifecycle of an HTTP |

|

Scopes a single bean definition to the lifecycle of a |

|

Scopes a single bean definition to the lifecycle of a |

A thread scope is available but is not registered by default. For more information,

see the documentation for

SimpleThreadScope.

For instructions on how to register this or any other custom scope, see

Using a Custom Scope.

|

The Singleton Scope

Only one shared instance of a singleton bean is managed, and all requests for beans with an ID or IDs that match that bean definition result in that one specific bean instance being returned by the Spring container.

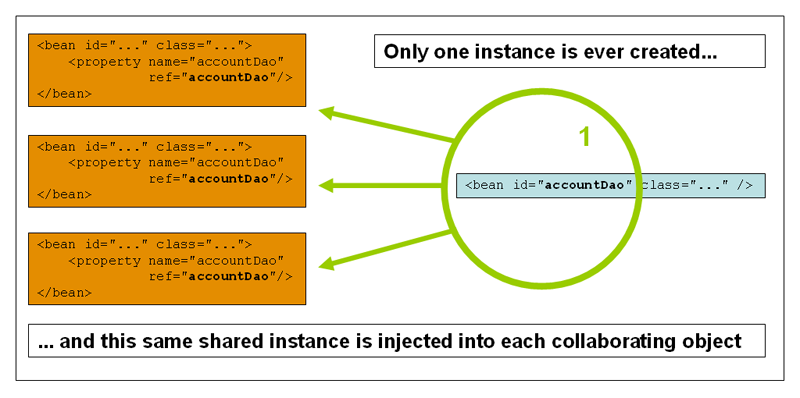

To put it another way, when you define a bean definition and it is scoped as a singleton, the Spring IoC container creates exactly one instance of the object defined by that bean definition. This single instance is stored in a cache of such singleton beans, and all subsequent requests and references for that named bean return the cached object. The following image shows how the singleton scope works:

Spring’s concept of a singleton bean differs from the singleton pattern as defined in the Gang of Four (GoF) patterns book. The GoF singleton hard-codes the scope of an object such that one and only one instance of a particular class is created per ClassLoader. The scope of the Spring singleton is best described as being per-container and per-bean. This means that, if you define one bean for a particular class in a single Spring container, the Spring container creates one and only one instance of the class defined by that bean definition. The singleton scope is the default scope in Spring. To define a bean as a singleton in XML, you can define a bean as shown in the following example:

<bean id="accountService" class="com.something.DefaultAccountService"/>

<!-- the following is equivalent, though redundant (singleton scope is the default) -->

<bean id="accountService" class="com.something.DefaultAccountService" scope="singleton"/>The Prototype Scope

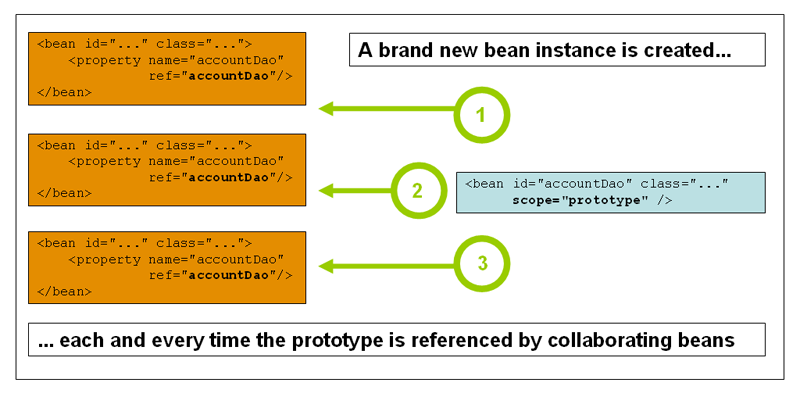

The non-singleton prototype scope of bean deployment results in the creation of a new

bean instance every time a request for that specific bean is made. That is, the bean

is injected into another bean or you request it through a getBean() method call on the

container. As a rule, you should use the prototype scope for all stateful beans and the

singleton scope for stateless beans.

The following diagram illustrates the Spring prototype scope:

(A data access object (DAO) is not typically configured as a prototype, because a typical DAO does not hold any conversational state. It was easier for us to reuse the core of the singleton diagram.)

The following example defines a bean as a prototype in XML:

<bean id="accountService" class="com.something.DefaultAccountService" scope="prototype"/>In contrast to the other scopes, Spring does not manage the complete lifecycle of a prototype bean. The container instantiates, configures, and otherwise assembles a prototype object and hands it to the client, with no further record of that prototype instance. Thus, although initialization lifecycle callback methods are called on all objects regardless of scope, in the case of prototypes, configured destruction lifecycle callbacks are not called. The client code must clean up prototype-scoped objects and release expensive resources that the prototype beans hold. To get the Spring container to release resources held by prototype-scoped beans, try using a custom bean post-processor which holds a reference to beans that need to be cleaned up.

In some respects, the Spring container’s role in regard to a prototype-scoped bean is a

replacement for the Java new operator. All lifecycle management past that point must

be handled by the client. (For details on the lifecycle of a bean in the Spring

container, see Lifecycle Callbacks.)

Singleton Beans with Prototype-bean Dependencies

When you use singleton-scoped beans with dependencies on prototype beans, be aware that dependencies are resolved at instantiation time. Thus, if you dependency-inject a prototype-scoped bean into a singleton-scoped bean, a new prototype bean is instantiated and then dependency-injected into the singleton bean. The prototype instance is the sole instance that is ever supplied to the singleton-scoped bean.

However, suppose you want the singleton-scoped bean to acquire a new instance of the prototype-scoped bean repeatedly at runtime. You cannot dependency-inject a prototype-scoped bean into your singleton bean, because that injection occurs only once, when the Spring container instantiates the singleton bean and resolves and injects its dependencies. If you need a new instance of a prototype bean at runtime more than once, see Method Injection.

Request, Session, Application, and WebSocket Scopes

The request, session, application, and websocket scopes are available only

if you use a web-aware Spring ApplicationContext implementation (such as

XmlWebApplicationContext). If you use these scopes with regular Spring IoC containers,

such as the ClassPathXmlApplicationContext, an IllegalStateException that complains

about an unknown bean scope is thrown.

Initial Web Configuration

To support the scoping of beans at the request, session, application, and

websocket levels (web-scoped beans), some minor initial configuration is

required before you define your beans. (This initial setup is not required

for the standard scopes: singleton and prototype.)

How you accomplish this initial setup depends on your particular Servlet environment.

If you access scoped beans within Spring Web MVC, in effect, within a request that is

processed by the Spring DispatcherServlet, no special setup is necessary.

DispatcherServlet already exposes all relevant state.

If you use a Servlet web container, with requests processed outside of Spring’s

DispatcherServlet (for example, when using JSF), you need to register the

org.springframework.web.context.request.RequestContextListener ServletRequestListener.

This can be done programmatically by using the WebApplicationInitializer interface.

Alternatively, add the following declaration to your web application’s web.xml file:

<web-app>

...

<listener>

<listener-class>

org.springframework.web.context.request.RequestContextListener

</listener-class>

</listener>

...

</web-app>Alternatively, if there are issues with your listener setup, consider using Spring’s

RequestContextFilter. The filter mapping depends on the surrounding web

application configuration, so you have to change it as appropriate. The following listing

shows the filter part of a web application:

<web-app>

...

<filter>

<filter-name>requestContextFilter</filter-name>

<filter-class>org.springframework.web.filter.RequestContextFilter</filter-class>

</filter>

<filter-mapping>

<filter-name>requestContextFilter</filter-name>

<url-pattern>/*</url-pattern>

</filter-mapping>

...

</web-app>DispatcherServlet, RequestContextListener, and RequestContextFilter all do exactly

the same thing, namely bind the HTTP request object to the Thread that is servicing

that request. This makes beans that are request- and session-scoped available further

down the call chain.

Request scope

Consider the following XML configuration for a bean definition:

<bean id="loginAction" class="com.something.LoginAction" scope="request"/>The Spring container creates a new instance of the LoginAction bean by using the

loginAction bean definition for each and every HTTP request. That is, the

loginAction bean is scoped at the HTTP request level. You can change the internal

state of the instance that is created as much as you want, because other instances

created from the same loginAction bean definition do not see these changes in state.

They are particular to an individual request. When the request completes processing, the

bean that is scoped to the request is discarded.

When using annotation-driven components or Java configuration, the @RequestScope annotation

can be used to assign a component to the request scope. The following example shows how

to do so:

-

Java

-

Kotlin

@RequestScope

@Component

public class LoginAction {

// ...

}@RequestScope

@Component

class LoginAction {

// ...

}Session Scope

Consider the following XML configuration for a bean definition:

<bean id="userPreferences" class="com.something.UserPreferences" scope="session"/>The Spring container creates a new instance of the UserPreferences bean by using the

userPreferences bean definition for the lifetime of a single HTTP Session. In other

words, the userPreferences bean is effectively scoped at the HTTP Session level. As

with request-scoped beans, you can change the internal state of the instance that is

created as much as you want, knowing that other HTTP Session instances that are also

using instances created from the same userPreferences bean definition do not see these

changes in state, because they are particular to an individual HTTP Session. When the

HTTP Session is eventually discarded, the bean that is scoped to that particular HTTP

Session is also discarded.

When using annotation-driven components or Java configuration, you can use the

@SessionScope annotation to assign a component to the session scope.

-

Java

-

Kotlin

@SessionScope

@Component

public class UserPreferences {

// ...

}@SessionScope

@Component

class UserPreferences {

// ...

}Application Scope

Consider the following XML configuration for a bean definition:

<bean id="appPreferences" class="com.something.AppPreferences" scope="application"/>The Spring container creates a new instance of the AppPreferences bean by using the

appPreferences bean definition once for the entire web application. That is, the

appPreferences bean is scoped at the ServletContext level and stored as a regular

ServletContext attribute. This is somewhat similar to a Spring singleton bean but

differs in two important ways: It is a singleton per ServletContext, not per Spring

ApplicationContext (for which there may be several in any given web application),

and it is actually exposed and therefore visible as a ServletContext attribute.

When using annotation-driven components or Java configuration, you can use the

@ApplicationScope annotation to assign a component to the application scope. The

following example shows how to do so:

-

Java

-

Kotlin

@ApplicationScope

@Component

public class AppPreferences {

// ...

}@ApplicationScope

@Component

class AppPreferences {

// ...

}WebSocket Scope

WebSocket scope is associated with the lifecycle of a WebSocket session and applies to STOMP over WebSocket applications, see WebSocket scope for more details.

Scoped Beans as Dependencies

The Spring IoC container manages not only the instantiation of your objects (beans), but also the wiring up of collaborators (or dependencies). If you want to inject (for example) an HTTP request-scoped bean into another bean of a longer-lived scope, you may choose to inject an AOP proxy in place of the scoped bean. That is, you need to inject a proxy object that exposes the same public interface as the scoped object but that can also retrieve the real target object from the relevant scope (such as an HTTP request) and delegate method calls onto the real object.

|

You may also use When declaring Also, scoped proxies are not the only way to access beans from shorter scopes in a

lifecycle-safe fashion. You may also declare your injection point (that is, the

constructor or setter argument or autowired field) as As an extended variant, you may declare The JSR-330 variant of this is called |

The configuration in the following example is only one line, but it is important to understand the “why” as well as the “how” behind it:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<beans xmlns="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans"

xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xmlns:aop="http://www.springframework.org/schema/aop"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans

https://www.springframework.org/schema/beans/spring-beans.xsd

http://www.springframework.org/schema/aop

https://www.springframework.org/schema/aop/spring-aop.xsd">

<!-- an HTTP Session-scoped bean exposed as a proxy -->

<bean id="userPreferences" class="com.something.UserPreferences" scope="session">

<!-- instructs the container to proxy the surrounding bean -->

<aop:scoped-proxy/> (1)

</bean>

<!-- a singleton-scoped bean injected with a proxy to the above bean -->

<bean id="userService" class="com.something.SimpleUserService">

<!-- a reference to the proxied userPreferences bean -->

<property name="userPreferences" ref="userPreferences"/>

</bean>

</beans>| 1 | The line that defines the proxy. |

To create such a proxy, you insert a child <aop:scoped-proxy/> element into a

scoped bean definition (see

Choosing the Type of Proxy to Create

and XML Schema-based configuration).

Why do definitions of beans scoped at the request, session and custom-scope

levels require the <aop:scoped-proxy/> element in common scenarios?

Consider the following singleton bean definition and contrast it with

what you need to define for the aforementioned scopes (note that the following

userPreferences bean definition as it stands is incomplete):

<bean id="userPreferences" class="com.something.UserPreferences" scope="session"/>

<bean id="userManager" class="com.something.UserManager">

<property name="userPreferences" ref="userPreferences"/>

</bean>In the preceding example, the singleton bean (userManager) is injected with a reference

to the HTTP Session-scoped bean (userPreferences). The salient point here is that the

userManager bean is a singleton: it is instantiated exactly once per

container, and its dependencies (in this case only one, the userPreferences bean) are

also injected only once. This means that the userManager bean operates only on the

exact same userPreferences object (that is, the one with which it was originally injected).

This is not the behavior you want when injecting a shorter-lived scoped bean into a

longer-lived scoped bean (for example, injecting an HTTP Session-scoped collaborating

bean as a dependency into singleton bean). Rather, you need a single userManager

object, and, for the lifetime of an HTTP Session, you need a userPreferences object

that is specific to the HTTP Session. Thus, the container creates an object that

exposes the exact same public interface as the UserPreferences class (ideally an

object that is a UserPreferences instance), which can fetch the real

UserPreferences object from the scoping mechanism (HTTP request, Session, and so

forth). The container injects this proxy object into the userManager bean, which is

unaware that this UserPreferences reference is a proxy. In this example, when a

UserManager instance invokes a method on the dependency-injected UserPreferences

object, it is actually invoking a method on the proxy. The proxy then fetches the real

UserPreferences object from (in this case) the HTTP Session and delegates the

method invocation onto the retrieved real UserPreferences object.

Thus, you need the following (correct and complete) configuration when injecting

request- and session-scoped beans into collaborating objects, as the following example

shows:

<bean id="userPreferences" class="com.something.UserPreferences" scope="session">

<aop:scoped-proxy/>

</bean>

<bean id="userManager" class="com.something.UserManager">

<property name="userPreferences" ref="userPreferences"/>

</bean>Choosing the Type of Proxy to Create

By default, when the Spring container creates a proxy for a bean that is marked up with

the <aop:scoped-proxy/> element, a CGLIB-based class proxy is created.

|

CGLIB proxies do not intercept private methods. Attempting to call a private method on such a proxy will not delegate to the actual scoped target object. |

Alternatively, you can configure the Spring container to create standard JDK

interface-based proxies for such scoped beans, by specifying false for the value of

the proxy-target-class attribute of the <aop:scoped-proxy/> element. Using JDK

interface-based proxies means that you do not need additional libraries in your

application classpath to affect such proxying. However, it also means that the class of

the scoped bean must implement at least one interface and that all collaborators

into which the scoped bean is injected must reference the bean through one of its

interfaces. The following example shows a proxy based on an interface:

<!-- DefaultUserPreferences implements the UserPreferences interface -->

<bean id="userPreferences" class="com.stuff.DefaultUserPreferences" scope="session">

<aop:scoped-proxy proxy-target-class="false"/>

</bean>

<bean id="userManager" class="com.stuff.UserManager">

<property name="userPreferences" ref="userPreferences"/>

</bean>For more detailed information about choosing class-based or interface-based proxying, see Proxying Mechanisms.

Custom Scopes

The bean scoping mechanism is extensible. You can define your own

scopes or even redefine existing scopes, although the latter is considered bad practice

and you cannot override the built-in singleton and prototype scopes.

Creating a Custom Scope

To integrate your custom scopes into the Spring container, you need to implement the

org.springframework.beans.factory.config.Scope interface, which is described in this

section. For an idea of how to implement your own scopes, see the Scope

implementations that are supplied with the Spring Framework itself and the

Scope javadoc,

which explains the methods you need to implement in more detail.

The Scope interface has four methods to get objects from the scope, remove them from

the scope, and let them be destroyed.

The session scope implementation, for example, returns the session-scoped bean (if it does not exist, the method returns a new instance of the bean, after having bound it to the session for future reference). The following method returns the object from the underlying scope:

-

Java

-

Kotlin

Object get(String name, ObjectFactory<?> objectFactory)fun get(name: String, objectFactory: ObjectFactory<*>): AnyThe session scope implementation, for example, removes the session-scoped bean from the

underlying session. The object should be returned, but you can return null if the

object with the specified name is not found. The following method removes the object from

the underlying scope:

-

Java

-

Kotlin

Object remove(String name)fun remove(name: String): AnyThe following method registers a callback that the scope should invoke when it is destroyed or when the specified object in the scope is destroyed:

-

Java

-

Kotlin

void registerDestructionCallback(String name, Runnable destructionCallback)fun registerDestructionCallback(name: String, destructionCallback: Runnable)See the javadoc or a Spring scope implementation for more information on destruction callbacks.

The following method obtains the conversation identifier for the underlying scope:

-

Java

-

Kotlin

String getConversationId()fun getConversationId(): StringThis identifier is different for each scope. For a session scoped implementation, this identifier can be the session identifier.

Using a Custom Scope

After you write and test one or more custom Scope implementations, you need to make

the Spring container aware of your new scopes. The following method is the central

method to register a new Scope with the Spring container:

-

Java

-

Kotlin

void registerScope(String scopeName, Scope scope);fun registerScope(scopeName: String, scope: Scope)This method is declared on the ConfigurableBeanFactory interface, which is available

through the BeanFactory property on most of the concrete ApplicationContext

implementations that ship with Spring.

The first argument to the registerScope(..) method is the unique name associated with

a scope. Examples of such names in the Spring container itself are singleton and

prototype. The second argument to the registerScope(..) method is an actual instance

of the custom Scope implementation that you wish to register and use.

Suppose that you write your custom Scope implementation, and then register it as shown

in the next example.

The next example uses SimpleThreadScope, which is included with Spring but is not

registered by default. The instructions would be the same for your own custom Scope

implementations.

|

-

Java

-

Kotlin

Scope threadScope = new SimpleThreadScope();

beanFactory.registerScope("thread", threadScope);val threadScope = SimpleThreadScope()

beanFactory.registerScope("thread", threadScope)You can then create bean definitions that adhere to the scoping rules of your custom

Scope, as follows:

<bean id="..." class="..." scope="thread">With a custom Scope implementation, you are not limited to programmatic registration

of the scope. You can also do the Scope registration declaratively, by using the

CustomScopeConfigurer class, as the following example shows:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<beans xmlns="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans"

xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xmlns:aop="http://www.springframework.org/schema/aop"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://www.springframework.org/schema/beans

https://www.springframework.org/schema/beans/spring-beans.xsd

http://www.springframework.org/schema/aop

https://www.springframework.org/schema/aop/spring-aop.xsd">

<bean class="org.springframework.beans.factory.config.CustomScopeConfigurer">

<property name="scopes">

<map>

<entry key="thread">

<bean class="org.springframework.context.support.SimpleThreadScope"/>

</entry>

</map>

</property>

</bean>

<bean id="thing2" class="x.y.Thing2" scope="thread">

<property name="name" value="Rick"/>

<aop:scoped-proxy/>

</bean>

<bean id="thing1" class="x.y.Thing1">

<property name="thing2" ref="thing2"/>

</bean>

</beans>

When you place <aop:scoped-proxy/> within a <bean> declaration for a

FactoryBean implementation, it is the factory bean itself that is scoped, not the object

returned from getObject().

|